Art as Activism: Mous Lamrabat

The Moroccan photographer discusses kitsch culture, democratizing art spaces and the importance of family with AJ Girard.

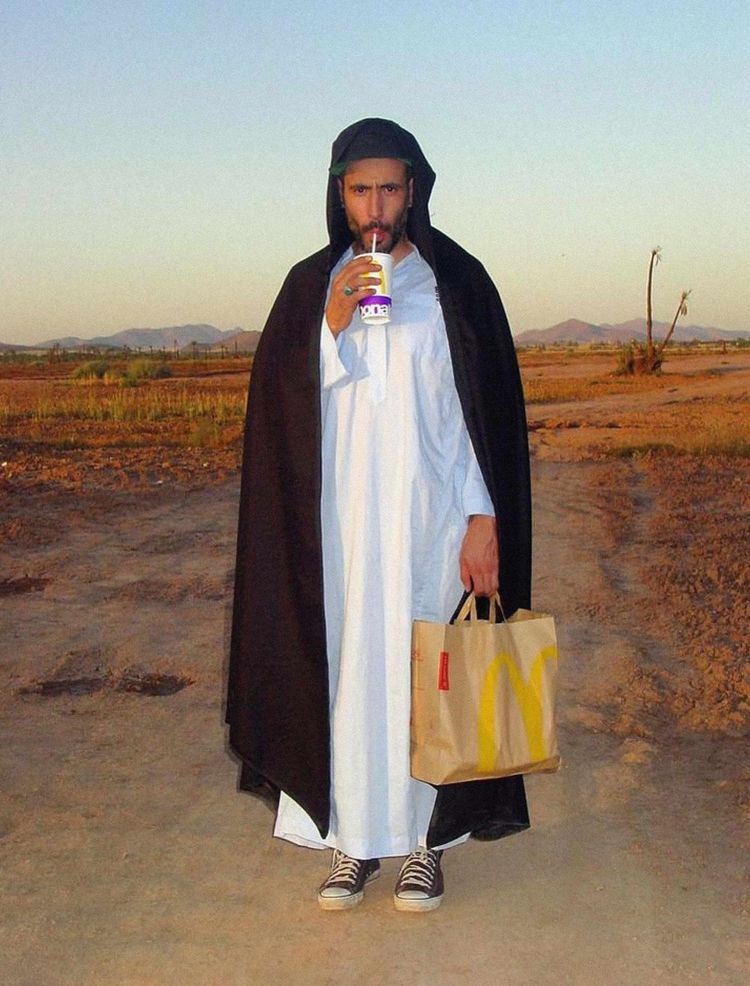

Mous Lamrabat’s work radiates with beauty, humor and searing color. Born in Morocco and based in Belgium (where his family relocated when he was a child), the photographer’s dreamlike practice is informed by his diasporic upbringing. Lamrabat’s imagery merges emblems of Western iconography with Middle Eastern culture—such as a Nike Swoosh emblazoned across a djellaba robe, or a yellow traditional Moroccan hat paired with glowing McDonald’s Golden Arches earrings. Through his wry and painterly lens, the artist navigates sensitive subjects such as race, religion and women’s rights, while ultimately relaying what he simply describes as a “message of love.”

Previously on view at Foam Amsterdam, Lamrabat’s solo exhibition “Blessings from Mousganistan” celebrated these principles, with a focus on joy and inclusivity. The show invited visitors into an imagined utopia shot in sun-drenched desert landscapes “where life is at peace and people are loved, no matter where you are from or where you are going.

Following the exhibition’s launch, Lamrabat sat down with curator and art historian AJ Girard for a freeform conversation spanning everything from kitsch culture and democratizing art spaces to the importance of family.

Tell me a bit about yourself.

I see myself as a creative person. Photography is the thing that works best for me; it’s a tool that was easy for me to master. Like a lot of artists, I started by doing commercial jobs but I struggled to find satisfaction in that kind of work, so I began doing my own thing. I remember going to an agency to show them all this commercial work, and then I said, "I also have these photos that I take for myself. I don’t know if you can do something with them," because I was quite insecure. Immediately, they swiped all the commercial photos off the table, and they said, "This is you. This is what you need to be showing the world, because this is unique." That’s kind of how it started rolling.

Now, hearing people talk about my work, it’s crazy to learn how so many people grew up in kind of the same way. It doesn’t matter how different you are; the color of your skin, religion or where you are in the world, there are so many similarities in how we grew up. That’s what I try to connect with in my work.

When I think about how I inserted myself into art history, it was really my family who shaped my approach, as they didn’t care about traditional notions of “good” or “bad” art. What are some of your earliest memories of being able to connect with your family around your craft?

With my parents, it’s similar, because they have no clue what the art world is. When I was in Amsterdam [for the Foam exhibition], my dad was like, “Are these people here for you?” And I said, “Yeah.“ “They like it?” I said, “I mean, I hope so.” Artists with the same kind of background that we have need to be patient [with family]. Obviously, every parent wants to be proud of their kids, so just keep involving them in what you do.

When I look at your work, especially when I think about the Nike Swoosh or the McDonald’s logo and things like that, that’s the world that my mom came from. She’s a very working-class person. She didn’t have time to explore all these conceptual plays in art. I think that I always try to work on projects that immediately give her the seat of control and power.

That’s the good part—when I can feel someone’s connected to what I’m doing. I’m the person who actually created, it but when it hangs on a wall in a gallery or a museum, people have the same kind of conversations that we are having right now and they can relate to something. This is the part that I’m excited about: how people look at the work. People bring their own perspectives and remember or recognize things. There’s this little feeling of nostalgia there. Nostalgia is my favorite feeling because it takes you back to a place of home.

Nostalgia is my favorite feeling because it takes you back to a place of home.

Mous Lamrabat

Institutions like museums and galleries have historically operated in an elitist and academic way, and then when you get to walk into them with your own experience of memory, it changes the atmosphere. That’s obviously one of the reasons why we do the work we do.

It’s funny that you say that because this is the first thing I ever said when I showed my work in these kinds of places. When I was young, I never went to a museum because it was not my place to be. I didn’t go in because I knew that people would look at me. In reality, maybe that wouldn’t have been the case, but that’s how it felt. Every exhibition I’m given, the first thing I do is take away the seriousness of the place because I know the people that enjoy my work are not only elite, rich people; there are 13-year-olds who enjoy my work. I want Moroccan kids to feel welcome.

I’m curious about your mom. Is she also an artist?

She’s creative, I’d say. If you give her anything, my mom will take a glue gun and bedazzle it. Once, I gave her African statues from my travels. I came back to visit her, and she’d put earrings on it. She makes it her own.

I love that. A lot of people who come from less-fortunate countries decorate everything they have. My mom was the same. Look at places like India, where the cars, the motorcycles, everything is decorated. In Morocco, it’s the same thing. There are big Nike logos on all the trucks and cars and, I don't know who came up with it, but there are Janet Jackson stickers everywhere. I’m like, “How did Janet Jackson get here?” I’m very interested in it. This has created a kitsch culture, which has become a very big source of inspiration these days. I’m not only talking about [the art world], but also the big fashion houses. Let’s take Balenciaga as an example; I think these guys are literally searching the internet for kitsch nostalgic things from way back.

You kind of gave me an emotional lightbulb moment right there. I was like, “Whoa, I don’t appreciate the upbringing that I had as much as I should sometimes,” when you say things like that. If the big fashion houses can appreciate it, then I should surely be able to see some value.

Anything that moves you, as a creative work, has succeeded, whether it’s a piece of art, or a runway show from Balenciaga where they brought something back that you totally forgot.

I love the way that you reinvent the things that I personally grew up with and can relate to, like fast fashion or fast food. This “give-it-to-me-now” culture.

It’s something that I looked up to when I was a kid. Sometimes I talk about this in interviews and it’s hard to make people understand how important these things were. I grew up in the ’90s; cool sneakers were the whole base of how you looked, but we couldn’t afford them so we put all these things on a pedestal. They became something that was not a logo anymore, but a symbol. I was so obsessed with these things, like even when someone bought a Nike shirt, I would ask them, “Can I have the tag?“ because it was a symbol.

Last year, I gave a tour to the Nike crew in Amsterdam, and my brother sent me a picture from when I was 16 that I’d completely forgotten about. I took the [Nike] tags off a shirt and stuck them to these little traditional hats that we wear in Morocco. When I saw this picture, I was like, “Oh my god, I was doing it already then.”

When I saw your work, I was really drawn to the cultural aspect of it, and how you felt comfortable playing with things that I always thought were rigid. Also, I think the way you glorify skin tone is so exciting. Usually I’m the only voice of color in any art space, and I don’t necessarily always have enough reflections back to me that having darker skin or having coarser hair is a form of beauty.

The thing is, if you are an artist of color and, for me, also Muslim, you carry a responsibility. Because whatever you do is not only you; you’re not an individual anymore. Sometimes it exhausts me because if I do something wrong, then it’s like [a reflection on] Moroccan artists or Muslim artists. I try to find ways to make the world know that I’m not representing my whole country or continent. I’m just one person. I have my good days and I have my bad days.

I hear so much of myself in what you’re saying and I see so much of myself in what you’re doing. I’m almost compelled to ask for advice. How do you get to become this person that you are now, where you have access to the world and have these insights?

In my eyes, I haven’t done anything yet. I think that is important: You’re never done. You’re never finished, because we still have, I hope, 30, 40 years to go. For me, my biggest reason to create is for this new generation of people with insecurities and identity crises, for people who don’t know where they belong. You always have to give something back. If you keep taking, then the universe will stop giving.

My biggest reason to create is for this new generation of people with insecurities and identity crises, for people who don’t know where they belong.

Mous Lamrabat

Art as Activism was conceptualized as a space for artists of color working in an art world filled with systemic injustices and inequalities. Other artists featured so far include Thelonious Stokes, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Esmaa Mohamoud, Murjoni Merriweather, Riley Holloway, Monica Kim Garza, Joseph Lee and Heather Agyepong.