Decoding the Visual Language of the ’90s and Early 2000s

Looking back at the ideas, technological innovations and multidisciplinary creatives that shaped skateboarding’s iconography.

Subversive graphics. Fisheye video footage. Hand-drawn logos. The skateboarding aesthetics we recognize today originated from a specific time and place: the West Coast of the United States during the late 20th century. A testament to DIY culture, the visual language of skateboarding was borne out of necessity, impulse and imagination. Whether it's the location of a trick, grainy video editing or customized footwear, every choice formed part of a larger optical narrative that has become one of the most inspirational forces in contemporary culture.

In the early ’90s, the action sports industry—based predominantly in Southern California—shrank, but new technologies emerged, creating a visual push and pull in skateboard graphics. Leaning into repurposed and often subverted corporate logos, album covers and obscure references, skateboarding moved beyond the tropes of the past. With the emergence of slick-bottom decks, photography could be incorporated and sublimated for the first time, opening new visual potential, especially when coupled with artwork made by skaters for skaters.

"Thrasher had ink-heavy paper that got on your fingers. It was more like a zine. Great, rough photos of people like 'Joey McSqueeb,' Gonz at Alcatraz."

Brian Anderson

SKATERS OWN THEIR IMAGE

As home computers became more accessible, a fusion of hand-drawn and digitally manipulated imagery led to crudely creative results. Highlights from this era include Natas Kaupas’ “Challenger” graphic from 1990, Tod Swank’s “Moon and Star” logo sketches from 1989, Ed Templeton’s debut “Crappy Graphics” and Andy Howell’s cartoon-inspired work for New Deal. In tandem, labels like FTC (For the City) emerged alongside the likes of Girl, Real and New Deal, helping define the aesthetics, style and DIY ethos of the scene.

Beyond the pro ranks, now-legendary artists such as Sean Cliver (Powell Peralta and World Industries), Marc McKee (World Industries) and Andy Jenkins (Girl)—all competent skaters in their own right—helped shape the visuals of the ’90s and 2000s with their incendiary deck designs that combined everything from horror and humor to satire and absurdity.

Now a little older, Cliver has reached new generations of skate fans through his collaborations with Supreme and Nike SB, while McKee’s Devil Man, Flame Boy and Wet Willy characters for World Industries remain iconic in the skate lexicon. Jenkins, for his part, founded the Art Dump collective of artists that have contributed to Girl over the years, simultaneously showcasing at prestigious exhibition spaces around the world.

Of course, it’d be impossible to talk about the crossover between pioneering skaters and artistic influence without mentioning Mark Gonzales, who drew the Blind logo by hand, offering an early look at his signature style that would go on to be hung in galleries in cities like Los Angeles, Paris and Tokyo.

GEARING UP

The ’90s saw skateboarding enter an era of accelerated progression. Tricks were invented, implemented and outdated at a rapid clip, with equipment following a similar evolution. Wheels shrank in size and trucks became lighter, while clothing became baggier due to the influence of rave, grunge and hip-hop culture.

As skaters in Northern California came together with East Coast transplants, outerwear became more of a focus, with Droors practically owning the category of hoodies and jackets by the middle part of the decade. Foundation and XLARGE, meanwhile, made forays into women’s clothing with Poot! and X-girl. In stark opposition to the West Coast’s warm weather, beanies even made a return, along with snapback baseball caps that replaced the painter’s hats of the ’80s.

“I was wearing skinny jeans, but noticed that a lot of the older skaters, the OGs, were wearing looser jeans,” remembers skateboarder and actor Olan Prenatt, who appeared in Jonah Hill’s mid90s. “Stereo was really creative. I loved the tie-dye designs and their logo. It wasn’t as big or well-known as brands like Spitfire or Baker, but that Stereo logo was something special.”

Looking back at the 2000s, Prenatt remembers certain pieces in particular. “Altamont was the coolest brand. Bryan Herman had the sickest corduroy pants in their collection. I also had a pair of Jim Greco’s pastel purple Krew cords. Back then, the Reynolds 3s were the coolest shoes to have. The colorways were insane.”

Together, these pieces formed an indelible image of skateboarding that remains in the public consciousness to this day, inspiring designers as far-reaching as Virgil Abloh, Demna Gvasalia and Kim Jones. In turn, these heavyweights have impacted a new wave of talent currently disrupting the luxury style climate, from Eli Russell Linnetz’s sun-bathed projections at ERL to the artistic sensibilities of Josué Thomas and Gallery Dept.

THE POWER OF PRINT

The introduction of video to skateboarding in the ’80s changed its entire landscape—but print’s power throughout the ’90s and early 2000s can’t be understated. Guided by the lens of J. Grant Brittain, Transworld focused primarily on Southern California with sprawling, artistic images.

In Northern California, Thrasher rarely veered from its “Skate and Destroy” ethos. Initially released in a mostly black-and-white periodical with occasional color hits, the magazine stood out against the slicker presentation of Transworld. Influenced by pioneers such as C.R. Stecyk III and Glen E. Friedman, Thrasher’s photographs were as artistic as those in Transworld, yet captured a different attitude and tone.

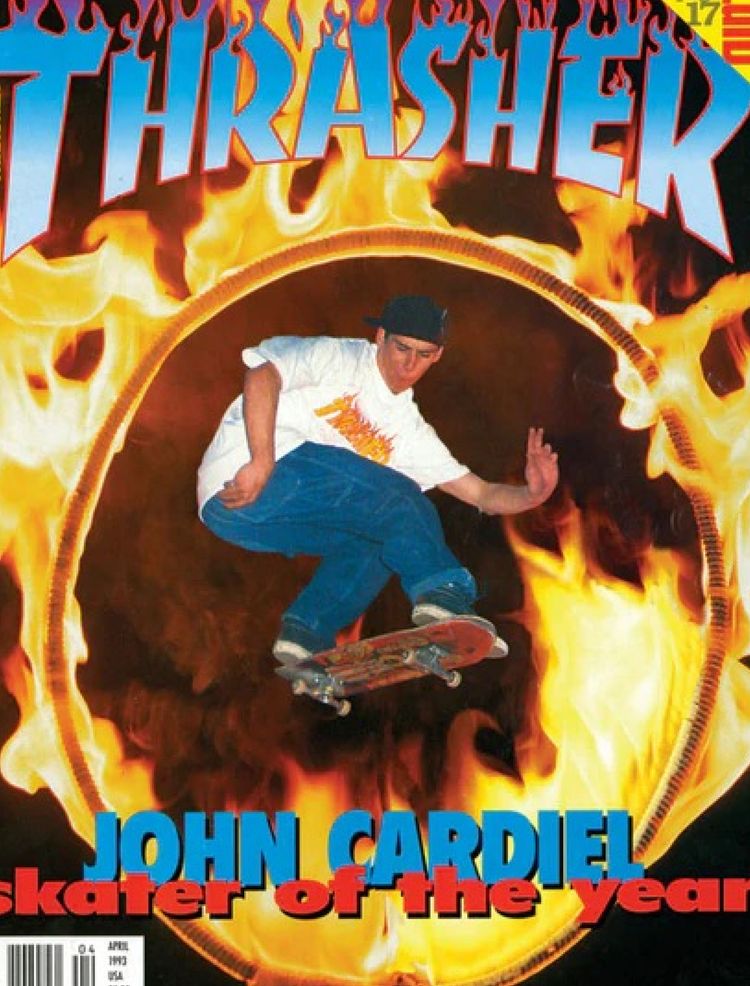

Thrasher would go on to play a significant role in defining the public perception of skateboarding with its uncompromising covers that defied authority and laid down a sense of youthful rebellion (see John Cardiel jumping through a ring of fire in 1993 or Brian Anderson surrounded by champagne, gold bars, dollar bills and flames in 2000).

"Thrasher had ink-heavy paper that got on your fingers. It was more like a zine. Great, rough photos of people like 'Joey McSqueeb,' Gonz at Alcatraz," says Brian Anderson in 2024. "But I loved seeing Chris Miller and all these other SoCal skaters in Transworld. The quality of the paper was nicer. Photos of all those vert ramps down the coast."

In 1992, Thrasher created sister publication Slap (some joked that the name stood for “Skaters Looking At Photos”) with East Coast transplant Lance Dawes in charge. Slap wasn’t exclusively street, but the magazine’s coverage and introduction of outside influences including hip-hop, graffiti and artful photography and design was right on the pulse of skateboarding’s progression.

FILM AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Famed for his signature use of flash and composition, Spike Jonze’s early work with magazines honed his critical eye, resulting in a signature aesthetic marked by streaks of light, multiple exposures and a nocturnal solitude that reflected the quiet tension of night sessions. Jonze’s video work, beginning with World Industries’ Rubbish Heap in 1989, gave him a new medium to explore his ideas, blending homage, candid off-board moments and irreverence with boundary-pushing skating, expressed in seminal films like Girl’s Goldfish from 1994.

Like Jonze, photographers and artists including Tobin Yelland and Thomas Campbell held a deep relationship with skating. While Campbell has become known for paintings, illustrations and sculptures, his photographs from the ’90s and 2000s created an important impressionistic view of skateboarding. Primarily a photographer, Yelland’s work on Antihero’s infamous Fucktards (1997) remains one of the rawest and most real depictions of skateboarding put to tape.

Meanwhile, a young Colorado transplant was about to shake things up. Atiba Jefferson’s catalog of images depicted milestones in skateboarding, informed by an understanding of how the environment that framed a trick added to the moment's gravity. A homie as much as a documentarian, Jefferson’s relationships with legendary pros created a unique dynamic that he carried into sport and commercial photography into the 2000s.

An early breakthrough for Jefferson came in the late ’90s when he and videographer Dan Wolfe outfitted Sony’s DCR VX-1000 camcorder with a Century Optics MK1 fisheye lens to capture Jeremy Wray in Santa Monica. Straight up the coast in the Bay Area, Aaron Meza was busy directing FTC’s influential Finally (1993) and Penal Code (1996) videos. Meza later contributed to edits from Girl and Chocolate, before leading Crailtap's early online content.

THE VISUAL LANGUAGE OF SKATING EVOLVES

The ’90s showed skateboarding had firmly detached itself from surfing with new visual aesthetics and ideas that evolved the video format. While Jonze dreamed up novel narratives and parodies, Jefferson leveraged new technologies and exploited natural landscapes to make projects pop.

With unprecedented graphics, magazines and photography, the decade was not only the most influential in skate history, but it offered the guiding framework for developing skateboarding’s visual identity as we know it today. The West Coast, more than anywhere else, fostered and nurtured a gestalt of creative energy, codifying an aesthetic that continues to exert an outsized impact on every aspect of the creative industries.

West Coast to the World uncovers how the subversive spirit of skateboarding resonates stronger than ever from its disruptive epicenter. Discover the exhibit here and explore skate culture’s origins.