Everything Connects at the Eames Office

How a small studio in a converted Venice Beach car garage run by a husband-and-wife duo created a new paradigm for creative culture worldwide.

In 1964, the World’s Fair came to Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, New York. Spread over 646 acres, 140 pavilions, 45 corporate exhibitions and 110 restaurants, the spectacle presented 51 million attendees with a vision of the future turbocharged by American culture and technology. The theme was “Peace Through Understanding,” dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe.” The 140-foot-high Unisphere, a stainless steel globe which recognized the inauguration of the Space Age and was the fair’s centerpiece, still stands in Queens today. IBM’s pavilion stood out as a futurist triumph. Its signage, information panels and corporate icons were wreathed in illustrations of doves, cherubim and baroque floral arrangements. Beneath a grove of steel trees, interactive exhibits sought to demystify the increasing presence of computers in everyday life.

Around a hundred IBM staff took part. They ran a puppet theater where Sherlock Holmes solved puzzles using binary logic. They demonstrated a Russian-to-English translation machine that could “read” Cyrillic and return with the English equivalent. There was a “typewriter bar” where guests printed postcards on electronic typewriters (quiet cousins to the louder mechanical devices with which the crowds would be familiar). Every 15 minutes, groups of up to 500 people filed onto an enormous grandstand to be hoisted almost 100 feet into the giant “Ovoid Theater,” an egg-shaped structure that housed a multiscreen film presentation called THINK, introduced by a live emcee.

Were it not for the curved, wall-mounted leather benches installed throughout the space (designed without legs to make life easier for cleaning crews), you could be forgiven for missing the mark of Charles and Ray Eames, who were commissioned to design the entire pavilion three years earlier.

Part I

OFFICE CULTURE

The creative legacy of husband and wife duo Charles and Ray Eames contains many wonders of 20th-century design. But even more lasting than the couple’s iconic Lounge Chair and Ottoman, or their home and studio in the Pacific Palisades, may be their influence on creative culture itself.

For more than four decades, the Eames Office was the center of Charles and Ray’s professional universe. Established in 1941 in a former car garage just minutes from Venice Beach, the office took design itself as a creative brief. How they would work was as interesting to them as what they would make. Today there is no design studio, fashion house, architectural office or research collective hoping to make lasting work that doesn’t owe them a debt of gratitude.

The model they pioneered persists because good design isn’t a question of moving fast and breaking things, but rather understanding the context in which you hope to intervene, studying the forces that will inevitably constrain you, and trawling through the archives to learn how we arrived at our current best efforts. There’s no point wasting time inventing solutions to problems that have already been solved.

“There was always this notion of pursuing an idea as much as you can,” says Eames Demetrios, director of the Eames Office, and Charles and Ray’s grandson. “Ironically, Charles is quoted saying, ‘Innovate as a last resort.’ What I think he meant is that if you innovate for innovation’s sake, you risk losing little but critical pieces of wisdom. I think they felt that if something was working well, they would prefer to focus on things that weren’t.”

Charles and Ray practiced what they preached—even if it cost them. When approached with the lucrative opportunity to redesign the Budweiser logo, they disappeared for six months before returning to America’s best-known beer brand, and saying, “Actually, we think you should keep your logo. It’s really good.” A cynic might argue they were at liberty to do so thanks to their furniture success, but this attitude predates breakthrough hits like the Organic Chair in 1940 and the plastic chair in early 1953.

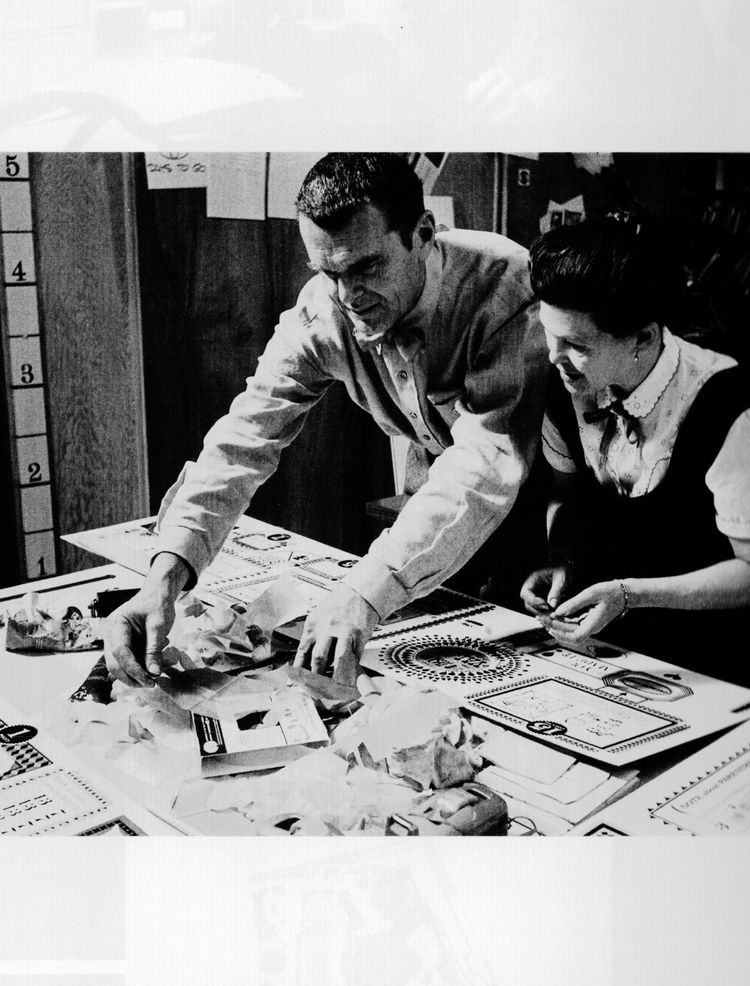

By the end of the 1940s, the couple had already made furniture and toys, fabrics and clothing, movies, exhibitions and a multimedia version of Hamlet (which was never released). The pair’s office was “a circus-like workspace,” Demetrios explains, strewn with furniture prototypes and typography experiments, a screening room and editing suite, a research library and moveable walls, all “glued together with a work ethic of tightrope-walking precision.”

Part II

EAMES AT THE FAIR

Grappling with the complexity of modern life was another goal for the Eames Office, where familiarizing the public with developments in science and technology was treated almost as a civic duty. This brought the duo into contact with giant companies like Polaroid, Westinghouse, Boeing and IBM; American corporations riding a post-war productivity boom, searching for ways to grow their markets but also to communicate the potential value of what they were doing.

In 1958, IBM commissioned the Eames Office to create a 10-minute short film for the Brussels World’s Fair. “The Information Machine” uses pencil-sketch animation to describe the main uses of a shiny, new and increasingly common device: the electronic computer. The video sounds a note of caution that would not sound out of place amid today’s disagreements over artificial intelligence (barring, of course, the gendered language): “With the computer as with any tool, the concept and direction must come from man. The task that is set and the data that is given must be man’s decision and his responsibility.”

IBM reconnected with Charles and Ray ahead of the 1964 New York World’s Fair, requesting that the Eames Office represent the company. The office would be responsible for the exhibition itself, as well as the films, signage, graphics and even furniture, continuing the partnership with IBM to bring the possibilities of the Information Age to an even larger audience. But initially, as with Budweiser, they said no.

“They originally recommended that IBM not do the fair,” says Demetrios. “The tradition of the World’s Fair had always been to bring people the cutting edge, and Charles and Ray feared it had become a marketing exercise.” In the end, IBM agreed to the Eameses’ request that the fair be “a gift of knowledge.” Charles began drawing up plans with help from his old friend, the architect Eero Saarinen.

Right from the start, plans included the marquee Ovoid Theater, inspired by the golf ball-like elements in IBM’s Selectric typewriters, which allowed them to install different fonts. THINK, the film playing inside, featured music by composer Elmer Bernstein and drew parallels between computers and information processing in humans, using activities such as party planning or driving as examples. Displays borrowed from “Mathematica: A World of Numbers … and Beyond”—an immersive exhibition from 1961 bringing together glossaries, infographics and historical timelines with toy-like spectacles to explore the mechanisms of mathematics—explained how it all worked.

The result was a playbook for how the Eames Office operated, sourcing the world’s most innovative minds to work together in service of a singular vision. Saarinen helped bring the concept of the IBM pavilion to life. Graphic designer Paul Rand developed a brochure with original typography. Bernstein elevated the moving imagery with Hollywood orchestration. Charles and Ray had innovated as a last resort, in turn constructing the prototype for a collaborative playground that would become a defining characteristic of creative culture in the years and decades to come.

Part III

EVERYTHING CONNECTS

Charles and Ray famously asserted that the role of a designer was akin to a host anticipating the needs of a guest. Responsibility for the wanderer is universal throughout all human cultures and any worthwhile thought experiment will consider how people will use it. Charles once said, “When you think about design as the bringing together of a number of materials and parts, letting them interact, and not as the expression of your own personality, the demand must be made that it answers the purpose, no matter how complex.”

The classic short film “Powers of Ten” commences at a picnic in downtown Chicago. The camera gradually pulls away from the scene, zooming out from capturing a single square meter, multiplying this by 10 every 10 seconds until the camera’s field of view stretches 1024 meters or 100 million light-years across. Next we are hurled back down to the park. The shot then moves down through a man’s hand to the subatomic level, 10-16 meters across, where we reach “the edge of present understanding.” As with the New York World’s Fair, the experience is visceral. You learn by being immersed in the conceit.

As most creative people will attest, ideas often languish in the drawer, on the shelf or in the hard drive, waiting for their moment to shine. A two-minute proto-“Powers of Ten” was produced by the Eames Office in 1968, simply to see if they could make the illusion work. It wasn’t a presentable film, but the idea was there, waiting to germinate further, a seed-like mixture of intention and play.

A new piece of work isn’t a failure just because it doesn’t make it into production. In professions like architecture, city planning and costume or store design, the completion of buildings, sets, developments and roads is just one of many tasks. Equally essential is the creation of concepts, presentations, proposals, models and competition entries, all of which may or may not be commercially or technically viable, but should be loaded with new knowledge and possibility.

Charles Eames died in 1978. Ray-Bernice Eames died in 1988, 10 years later to the day. “Charles and Ray were constantly trying to improve their designs, and they wanted us to continue that,” Demetrios says. “For example, after Charles’ death it became clear the Brazilian rosewood used in the Lounge Chair wasn’t being harvested sustainably. It took about seven years to develop Santos Palisander, which is a different type of rosewood and can be sustainably farmed. But that didn’t come out until after her death.”

A similarly gradual evolution applies to many of the Eameses’ innovations. Exploratory work on molding plywood formed the basis for splints and stretchers used by the U.S. Navy during World War II. The process was in turn used to make a toy elephant for children, a popular product after the war was over. It also gave them their first popular chair. As Charles observed, eventually everything connects.

The spirit of the Eames Office remains a case study for popular engagement with a changing world. It’s an example for today’s educators, corporate giants, legislators and cultural institutions. The stainless steel Unisphere in Flushing Meadows Park may be less shiny than it was. Likewise, 1960s ideas about a finite globe from which humanity would springboard across the cosmos are tarnished in contemporary eyes. But the working methods of Charles and Ray Eames continue being iterated upon in digital archives, research platforms and exhibitions—wherever people try to seed ideas and innovations that last.

Shop GREATEST 09 here and discover the issue's cover stories, including sub, Yoon Ahn, Peso Pluma and Tyshawn Jones.